How long does it take to make a Shrubconscious “creature?”

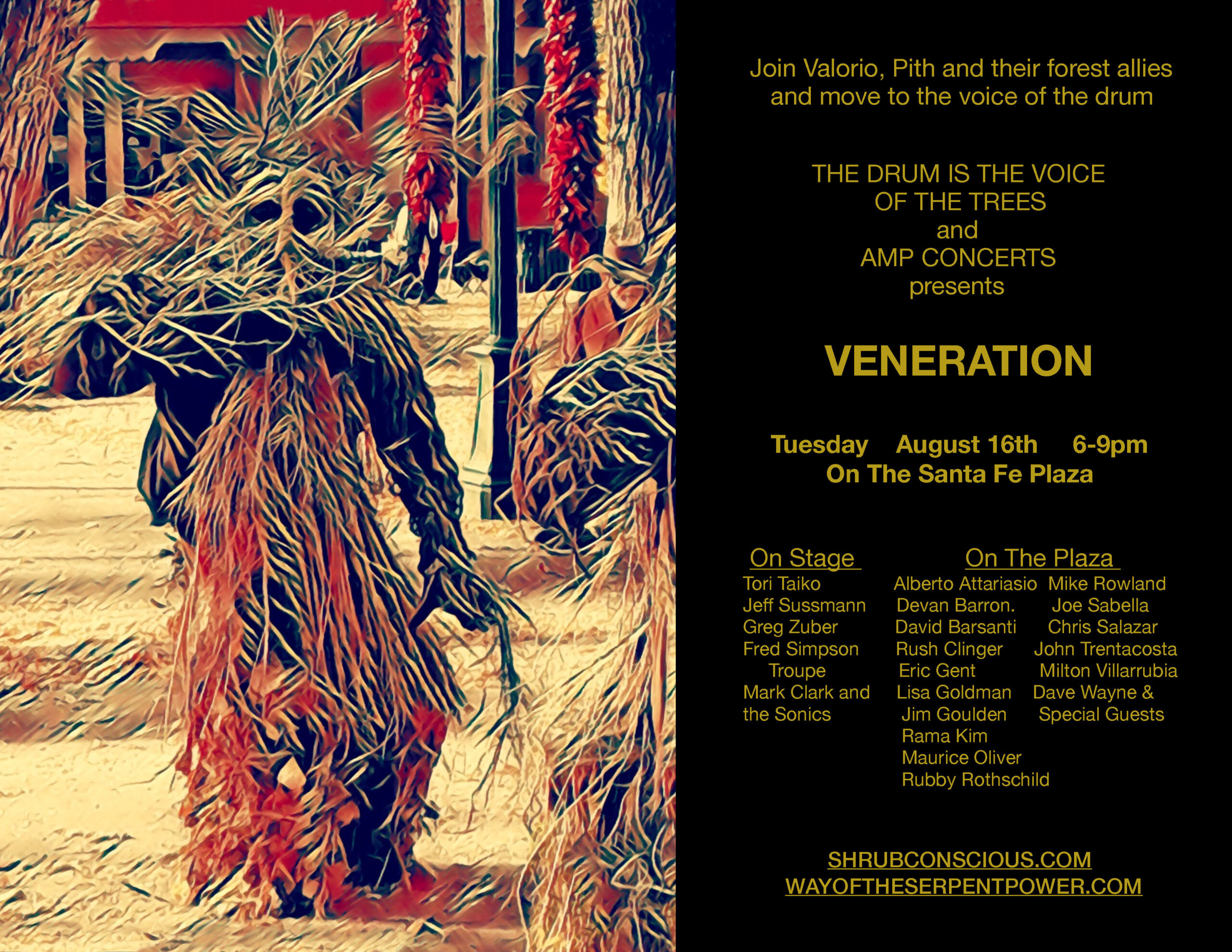

For the past six months I’ve been making two larger-than-life fantasy figure costumes out of tuft grass, burlap and hemp twine. I would guess that I have put in between 600 and 800 of actual work so far and perhaps two or three times that if I count time spent figuring things out in my head. As a lifetime craftsman, I’ve found the studio work stimulating and relaxing for the most part but not without its challenges. I sing, talk to Holy Spirit, listen to music, recorded books, or podcasts when I’m doing the repetitive tasks. While I’ve used a lot of indigenous plants in my sculptures and costumes, never have jute and tuft grass been featured, so I have to invent as I go because there is a limited time until the performance and that means the experimentation must be focused on immediate solutions. I think about the past, when our predecessors had to make garments and costumes out of plants. There must be some remnant of their ingenuity that I can draw from in my DNA. And we also trust that everyone who sees them will find them familiar.

Do you collaborate on these costumes?

The first two costumes which were used in “Scorched Ladders” were created by a professional costumer, Tatyana de Pavlov. Before moving to New Mexico, Tatyana was brought up in the arts working on costumes for the opera. The costumes came out beautifully, on time, and in budget. We couldn’t have been more pleased, and the creatures she came up with: “Pith” and “Valorio” have delighted audiences ever since, even winning the Meow Wolf Monster Battle Grand Prize in 2019.

The next costume enlisted the skills of another pro, Joanna Becker. She, too, provided a costume above and beyond our expectations. It was completed last year and marks the beginning of my experiments with tuft grass. It’s quite intricate, with a mechanical component achieved with willow branches. I won’t give away what it does, but it is sure to delight the crowd.

How did your concept of these creatures develop?

After watching the artists who wore these first costumes perform scenes in front of the camera, it became my desire to create something lighter and easier that could be worn in more populated settings and events. I had been using Chamisa and Apache Plume, but grass is so lightweight and abundant. Because it requires minimal care and water, tuft grass takes up a lot of space in our yard, so I started saving it at the end of the season. When bunched together, it can be incredibly strong. I was immediately impressed with grass as a material but it was not a straight forward path from then to where we are now. At first, I designed the entire costumes to be supported by the head, almost a hat, that reached down to knee level. As each costume grew larger than life-sized, as was my aim, this became an issue. They turned out to be substantially lighter than the prior costumes, but were, unfortunately, more cumbersome to move around in, and hard to see out of. So I had to cut them into pieces and refashion the parts into components.

Did you have any down time in the creation process?

There was a two-week period where I didn’t touch the costumes, but I thought about them every day. In several imaginary processes, I cut and reassembled them for more ease of wear and mobility. It was difficult to make myself cut up the work that I had probably spent 200-300 hours making already, but when I finally did, it felt right.

Several hundred stitches later, the parts were realigned and functioning properly. The artist wearing them can move their limbs and joints more normally, plus enjoy improved visibility. In comparison to the former three costumes, these latest two feel nearly weightless. So three key objectives have been achieved, lightness, delightfulness, and mobility.

What do you think about the creative process as a whole?

I can’t think of it as a single process. The creative process moves to and fro along a continuum between vacuums of isolated searching and surging hydrants of enthusiasm. There’s time spent dreaming up ideas, then working them out in my notebook. Talking about them, doing research, gathering materials, accumulating collaborators along the way. That is a representative cross section. After decades of practice, I’m still learning to get out of my own way and let the unexpected encounters and unforeseen accidents inform the work.

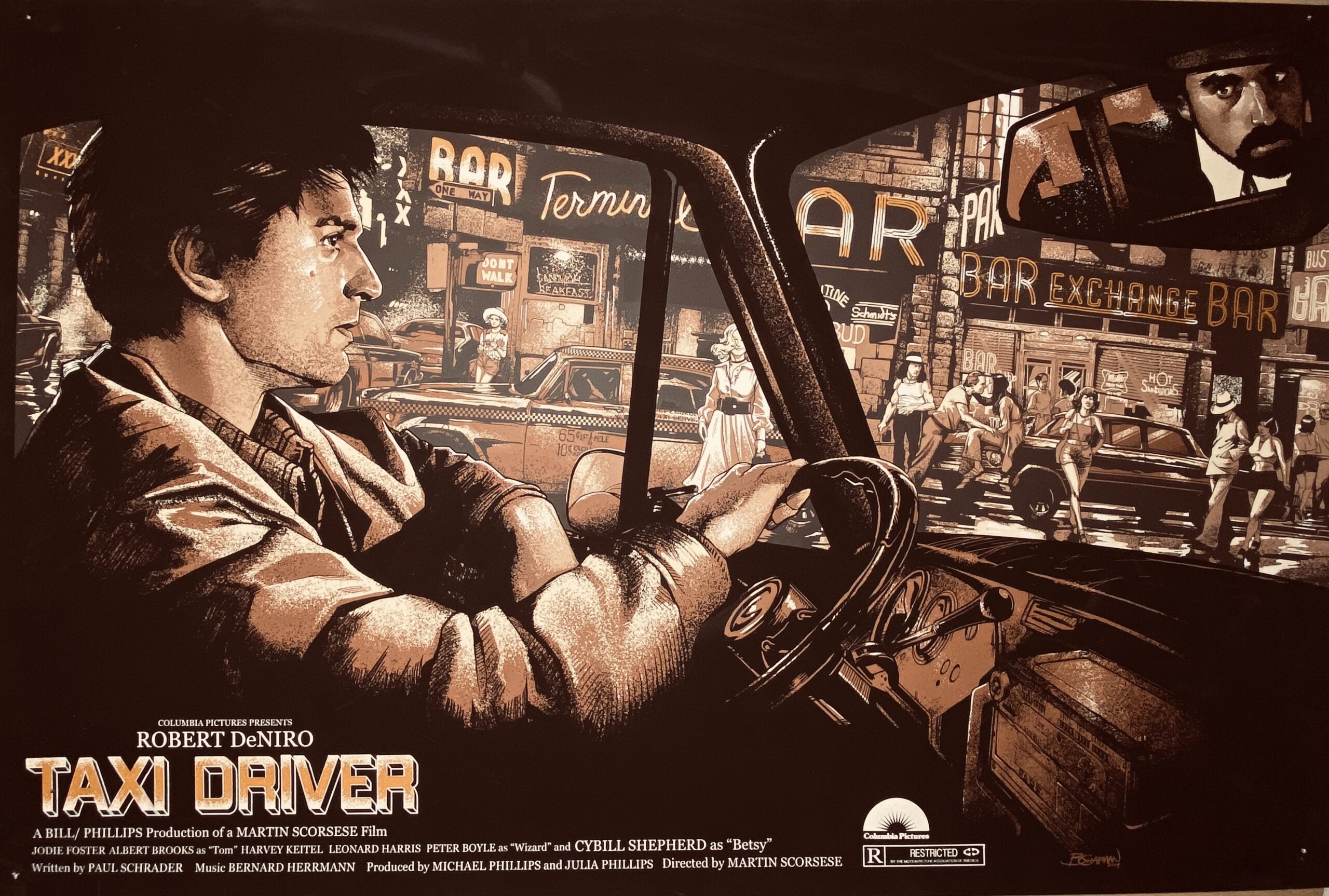

Promoting the work when its finished is an aspect of the process that I have much to learn about still, so thank you Mel, for this interview for which you have so generously devoted your time. I always try to leverage everything I do by creating outputs from all my projects in 2D, 3D and HD. That’s a lot of moving parts and it gets overwhelming sometimes. You’re an integral part of this. Whenever I have worked on a shrub sculpture or costume for any length of time, I become conscious of the absurdity of what I’m trying to achieve. Then all these wonderful people get involved and we’re just doing our spiritual practice together, being creative and communing with each other. So, for instance, now here we are gathered to make an offering, for the well-being of all by honoring the Earth.